B

-

Barbara Balmer RSA RSW

-

Edward Bawden RA

-

Gilbert Bayes FRBS

-

Robert Henderson Blyth RSA RSW

-

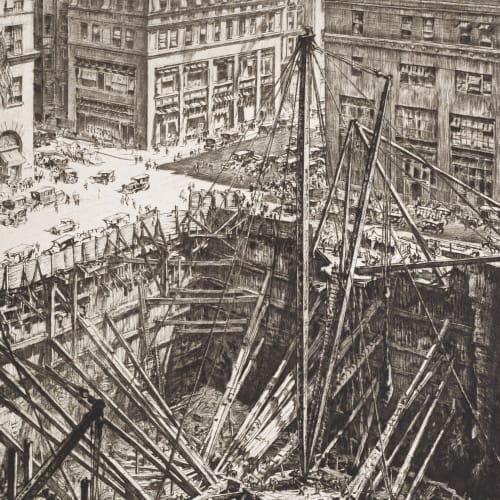

Sir Muirhead Bone HRSA HRWS

-

Sam Bough RSA RSW

-

Gerald Leslie Brockhurst RA

-

Robert Brough RA ARSA

-

Frederick Burrows

-

John Byrne RSA

C

-

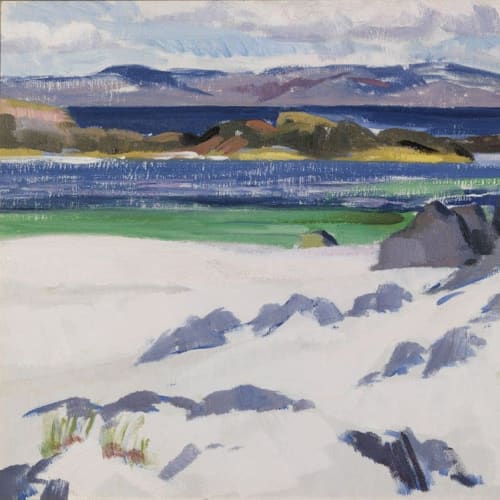

Francis Campbell Boileau Cadell RSA RSW

-

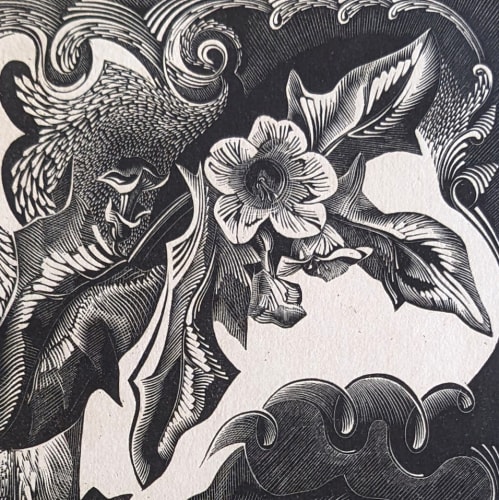

Katharine Cameron RWS RE

-

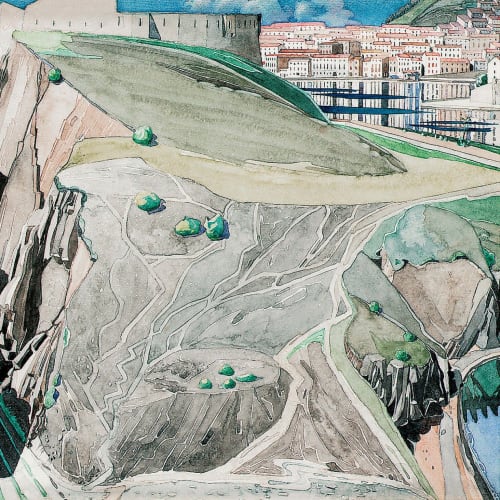

Sir David Young Cameron RA RSA HRSW RE

-

Alexander Carse

-

Sir George Clausen RA RWS

-

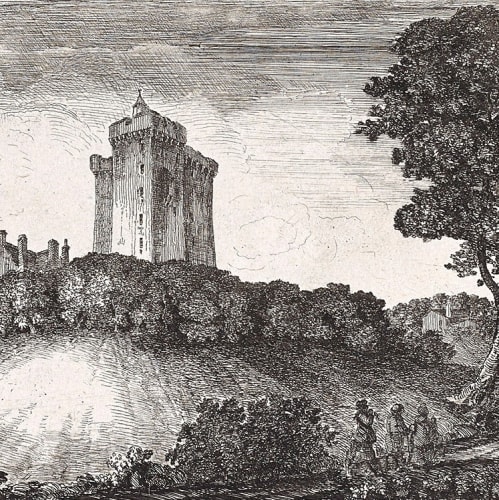

John Clerk of Eldin

-

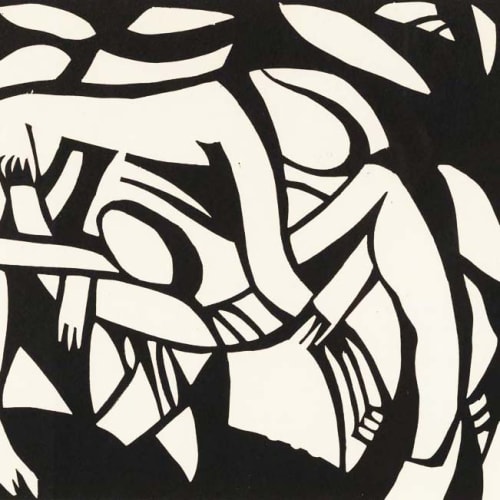

Prunella Clough

-

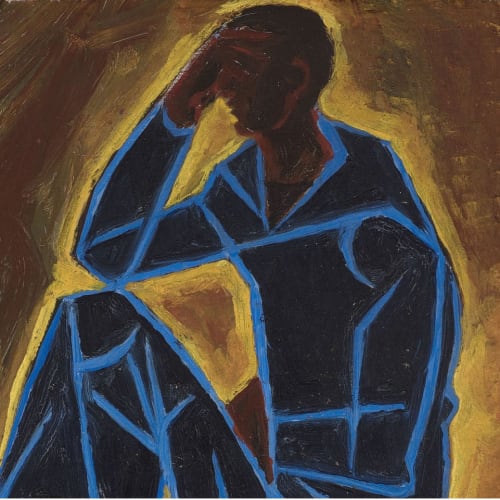

Robert Colquhoun

-

Waistel Cooper

-

Daniel Cottier

-

James Cowie RSA

-

Joseph Crawhall RSW

-

John Craxton RA

G

-

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

-

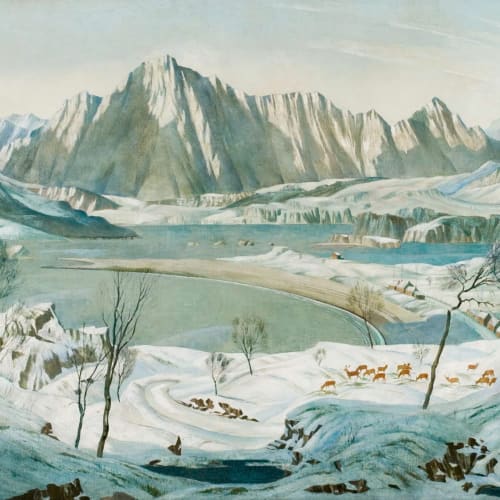

Sir William Gillies RA RSA PRSW

-

Gluck

-

Edward W. Godwin

-

Sir Herbert James Gunn RA

-

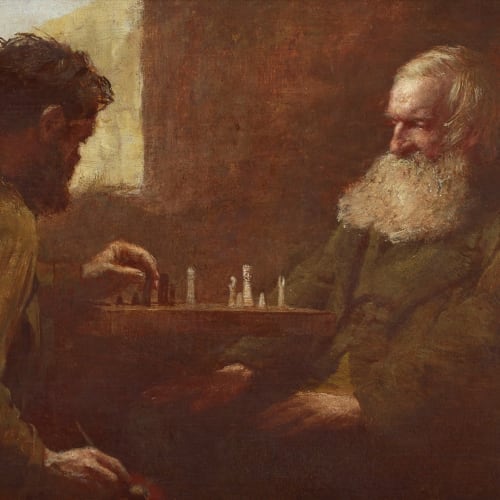

Sir James Guthrie HRA PRSA HRSW

H

-

George Henry RA RSA RSW

-

Barbara Hepworth DBE

-

Gertrude Anna Bertha Hermes OBE RA

-

Edward Atkinson Hornel

-

George Houston RSA RSW

-

John Houston OBE RSA

-

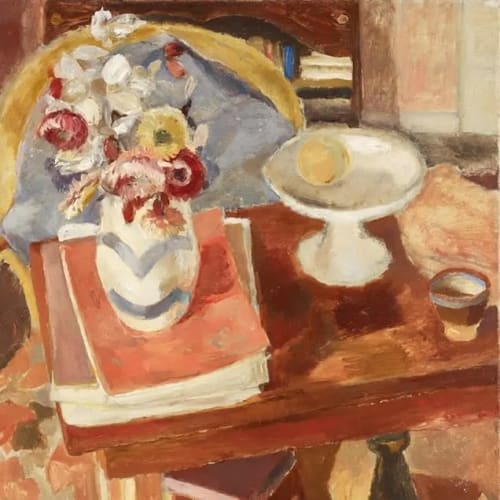

George Leslie Hunter

-

Kenny Hunter

M

-

Robert Macbryde

-

Charles Hodge Mackie RSA RSW

-

Charles Rennie Mackintosh

-

Margaret MacDonald Mackintosh

-

Will Maclean RSA

-

Iain Macnab

-

Harrington Mann

-

Kenneth Martin

-

Oscar Marzaroli

-

James McBey

-

Horatio McCulloch RSA

-

James McIntosh Patrick OBE RSA

-

John McLean

-

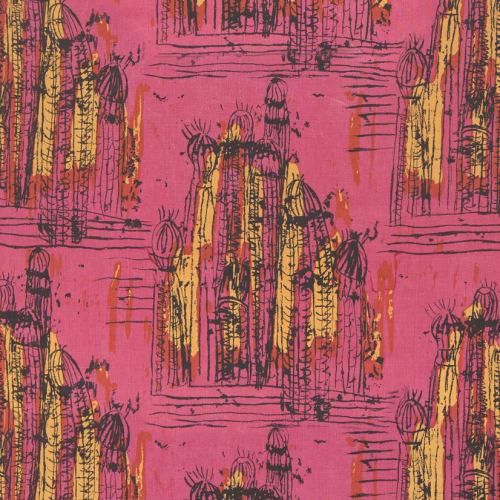

Althea McNish

-

William McTaggart RSA RSW

-

Arthur Melville ARSA RSW

-

John Minton

-

William De Morgan

-

Talwin Morris

N

-

Paul Nash

-

Alexander Nasmyth HRSA

-

C. R. W. Nevinson ARA

-

Algernon Newton RA

-

Ben Nicholson OM

-

Sir William Nicholson

P

-

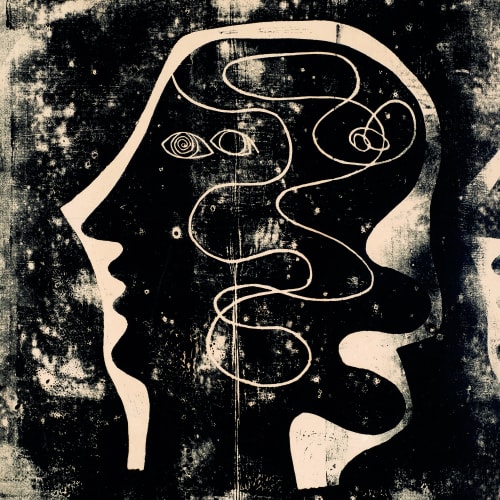

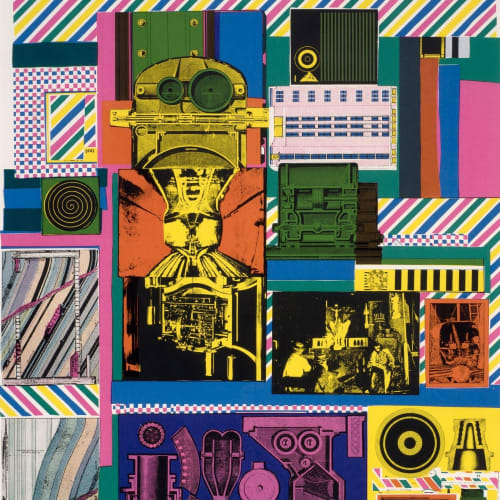

Sir Eduardo Paolozzi CBE RA

-

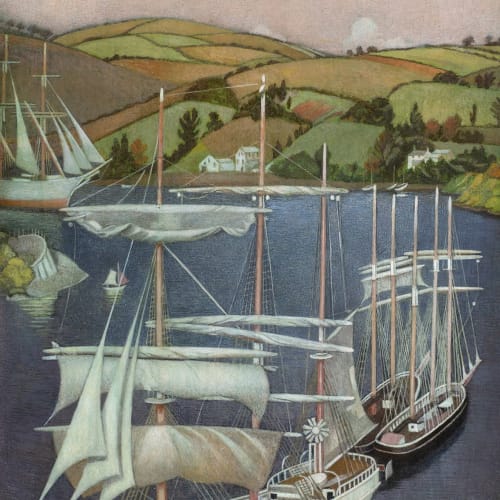

James Paterson RSA PRSW

-

Waller Hugh Paton RSA RSW

-

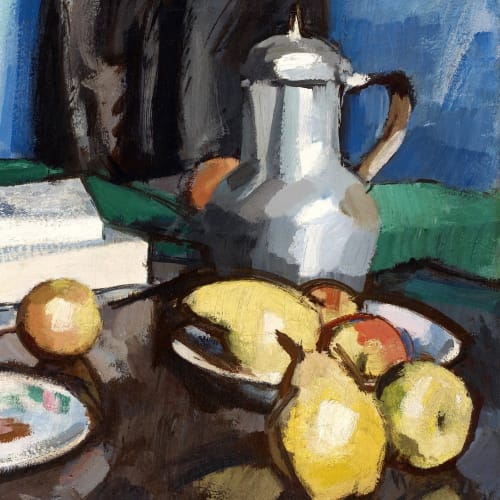

Samuel Peploe RSA

-

John Piper CH

-

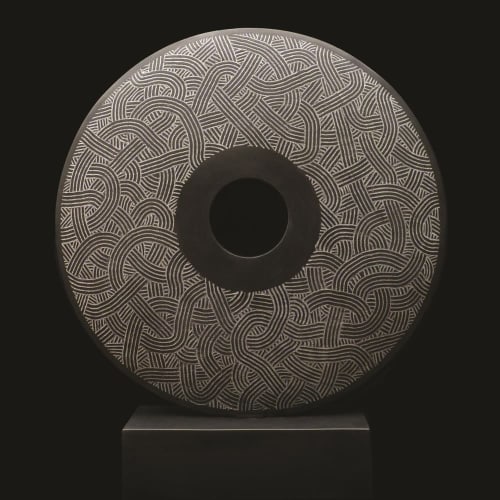

Tim Pomeroy

-

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin

R

-

Sir Henry Raeburn RA

-

Allan Ramsay

-

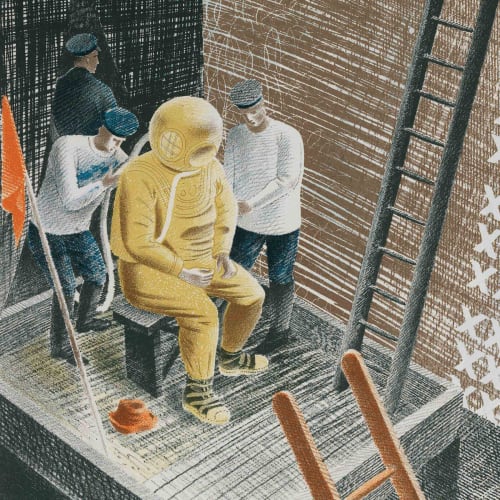

Eric Ravilious

-

Anne Redpath OBE ARA RSA

-

David Roberts RA

-

Eric Robertson

-

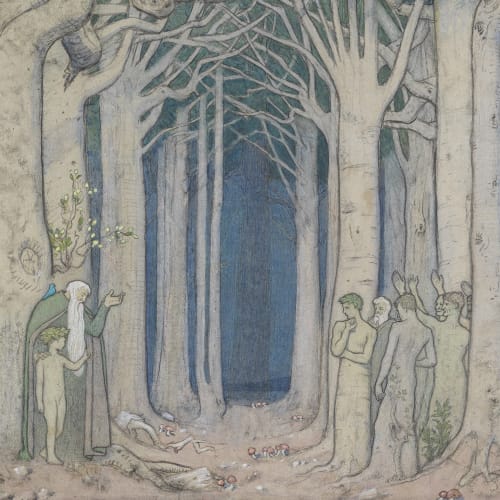

Frederick Cayley Robinson RWS

-

Alexander Runciman

S

-

Ron Sandford

-

Walter Richard Sickert

-

Joseph Edward Southall

-

Gilbert Spencer RA

-

Sir Stanley Spencer CBE RA

-

Sir John Robert Steell RSA

-

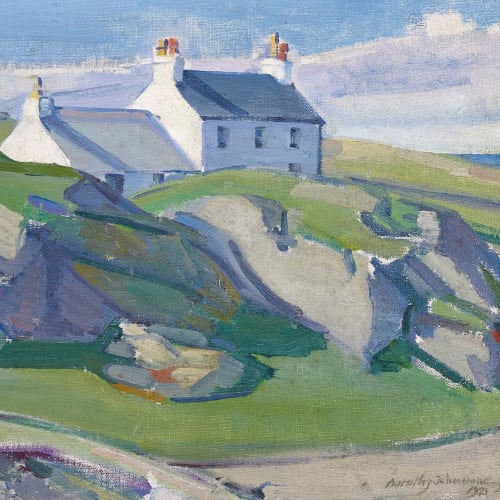

Alick Riddell Sturrock RSA

-

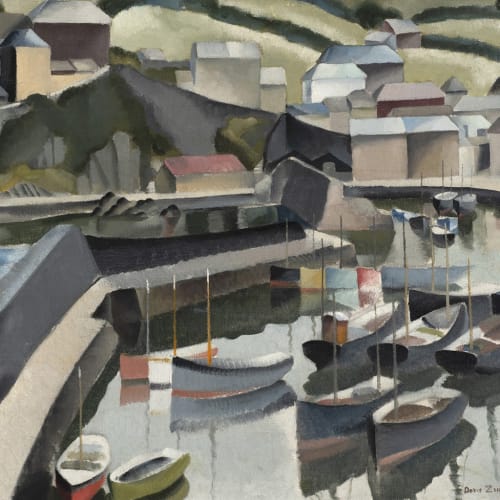

David Macbeth Sutherland RSA