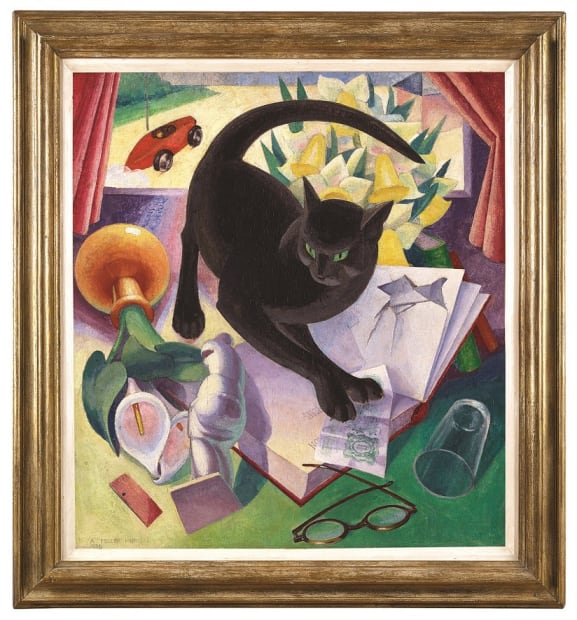

AGNES MILLER PARKER: ARTIST IN FOCUS

-

‘that clever couple from scotland who believe in cubist methods’

hugh macdiarmid (1892-1978) on miller parker and mccance

-

Agnes Miller Parker’s seemingly innocent still life brings to the fore concerns and debates around women’s rights of the time. Whether it points to the artist’s relationship with her husband, fellow Vorticist William McCance (1894-1970), is conjecture. What we can be certain of however, is that Miller Parker was unequivocally a female anomaly of her time, as an independent thinker who was unafraid to reject societal norms and conventions of womanhood.

-

-

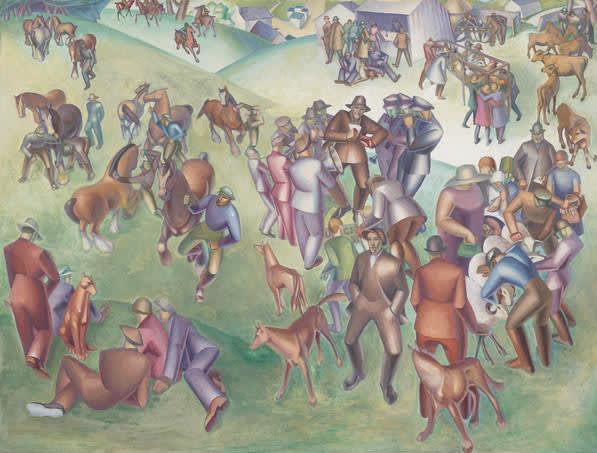

The Horse Fair, 1928

Agnes Miller Parker

National Galleries Scotland (long term loan), © The Artist's Estate

-

Portrait of Agnes Miller Parker, 1918

William McCance

National Galleries Scotland, © Margaret McCance

-

She never remarried; in this retrospective light, we could interpret The Uncivilised Cat as a visual reinforcement of Miller Parker’s desire for independence, both professionally as a woman artist, and personally as a liberal believer in women’s rights and female sexuality.

-

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP TO RECEIVE THE FINE ART SOCIETY'S JOURNAL